Following the recent changes to the permit system for tracking Rwanda’s wild mountain gorillas, the why and wherefore of travel restrictions is at the forefront of our mind. It’s not just Rwanda making the changes: Venice is reputedly considering a cap on visitors and constraints on cruise ships to protect the already fragile city.

Here we look at the brand-new changes introduced to visiting Machu Picchu, and examine three other destinations — Bhutan, Borneo and Australia’s Arnhem Land — which require a little jumping through travel loopholes. In all of these cases, there are solid conservation reasons for why such stringent entry systems or permits exist. We explain what they involve, and how they can help to create a more enriching experience for visitors.

Mountain gorilla tracking in Rwanda

Making your way through dense rainforest, you carefully step over roots, weave through tree trunks and beat back stubborn branches. The sense of anticipation builds with each step, but the sight of your first mountain gorilla still comes as a surprise. A troop of around 15 sit before you munching on leaves and keeping watch in the trees, their dark hair glistening from the moisture in the air. And then you simply watch.

There are fewer than 900 mountain gorillas left in the wild. Seeing them in their natural montane rainforest habitat is a rare privilege: troops can only be visited by those holding a pre-arranged, non-refundable permit.

In Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park — home to around half of the world’s mountain gorillas — just 96 permits are handed out each day, with one permit granting you an hour with the gorillas. This year, their price doubled to US$1,500 as more land needed to be purchased and protected for the park’s gradually growing mountain gorilla population.

These permits are crucial to the survival of this fragile species. With just eight people able to visit a troop at any one time, there’s less disruption to the gorillas’ natural environment. The gorillas are also susceptible to catching human diseases, so it’s important to keep contact to a minimum.

Finally, money from the permits will not only help to extend and maintain the gorillas’ natural habitat, without which they’d become extinct in the wild, but also empower local communities through the funding of development projects, encouraging them to conserve the park’s natural assets.

Arnhem Land, Australia

In Australia’s north — the ‘Top End’ — lies a little-explored wilderness of rock and water. Arnhem Land sprawls over a sandstone massif saturated with wooded swamps of paperbark trees and wetlands braided with water lilies, while vast eucalypt forests are broken up by jagged scarps. Among it all are remote outstations, the homes of Indigenous Australians for whom this land is a protected reserve, allowing them to live as they wish, often in accordance with the old ways. Enigmatic and unspoiled, seeing Arnhem Land for yourself requires a permit from the traditional landowners, mostly Yolngu people.

The regulations not only work to preserve Aboriginal privacy, heritage and land ownership. They also reduce footfall, warding off over-curious outsiders from riding roughshod over ecologically pristine landscapes and hallowed ceremonial grounds.

By far the best way to visit this quasi-country-within-a-country is through a two-day safari with an operator such as Davidson’s. They have longstanding relationships with the land’s custodians and will arrange your entry process in advance. Crucially, they’ll be able to take you to specific sites to which the elders have granted them access. We find this makes for intimate, intense encounters with the land and its stories.

You’ll see rock art in pristine condition — intricate terracotta-red, yellow and even cobalt-blue paintings of major Dreaming figures, including the rainbow serpent. You’ll visit Aboriginal-run arts communities, cruise billabongs in search of freshwater and estuarine crocodiles, and may even witness ancestral mummified remains laid among gaps in rock — a site so sacred, photography is banned.

Machu Picchu, Peru

From its improbable setting on a mountain saddle in the middle of the Andes to its cosmically positioned — but eternally enigmatic — stone structures, this skeletal village-sized Inca citadel draws thousands of sightseers a day. So many, in fact, that UNESCO started to panic, and the Peruvian Government, it seems, have finally heeded their calls. From July this year, the regulations around visiting the Machu Picchu have tightened. These new rules seem provisional in nature and are likely to change again in the near future, but this is how we understand it at the time of writing:

Visitors will be assigned a timed slot (either 6am until 12 noon, or 12 noon till 5:30pm; visitors wishing to stay all day will need to pay for entry twice). A guide will accompany you at all times around the site, and in theory you’re meant to stick to one of three set circuits rather than wander at will (though in practice we haven’t seen this enforced yet — there are simply arrows trying to direct the flow of visitors.) Permits must be arranged in advance of your arrival if you want to climb Machu Picchu Mountain, which lies to the south of the site, or Huayna Picchu, the more cone-like peak that frames the ruins to the north.

The reason behind it all? Erosion, and the subsequent need to reduce footfall, is a large part of it, but also the fact that so many visitors swarming over the site’s terraces and narrow pathways is an increased safety risk — particularly when it comes to climbing the two mountains. You don’t really want to negotiate the steep, slender paths of either mountain alongside large tour groups hurrying their way up and down.

Ultimately, though, these new restrictions won’t dilute your experience. Spending all your time with a knowledgeable private guide is no bad thing: it allows you to get as much as possible out of your visit, as they’ll explain all about Inca stonemasonry, and everything that archaeologists and anthropologists have managed to glean (so far) from the impassive remains.

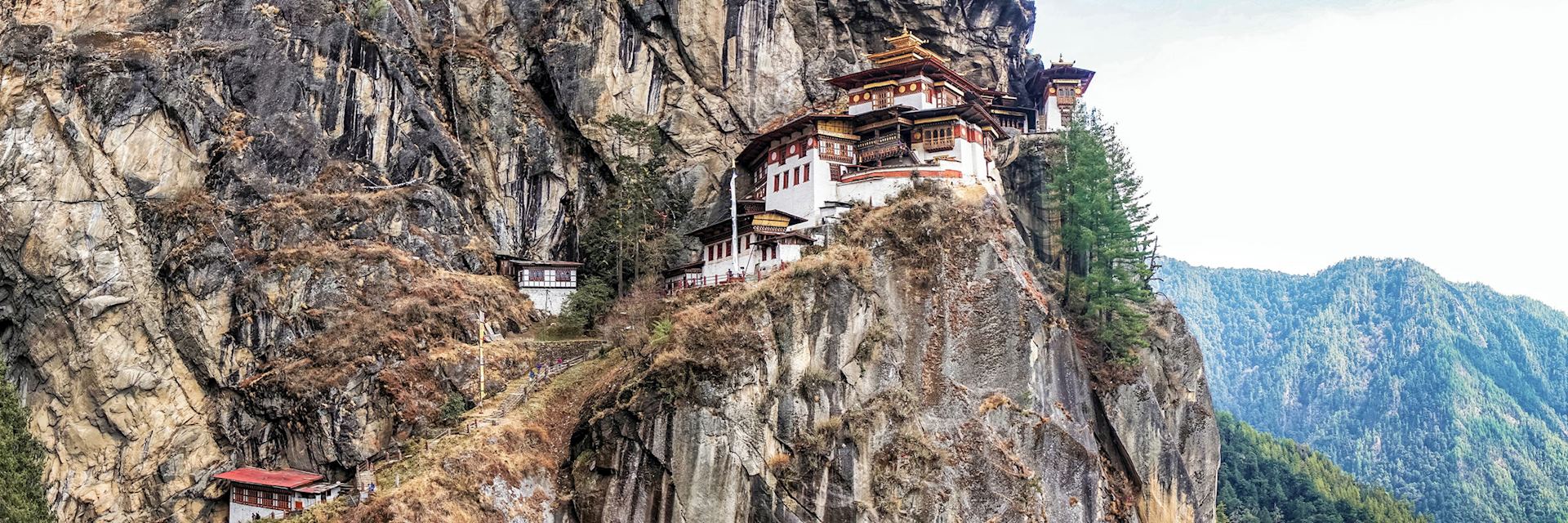

Bhutan

Bhutan is a land apart, and not simply because of its topography. This tiny kingdom is cradled between Himalayan peaks and paddy fields cascading downward to farmed valley floors. With over 60% of its land forested (partly thanks to forward-thinking environmental policies) parts of it are challenging to reach.

But the main restriction on travel to Bhutan is touching down there in the first place — only two airlines fly there, and there’s no daily service — along with the need for a government-issued visa. Audley will arrange this for you in advance, but the country places certain conditions on virtually all foreign visitors. Everyone must pay a minimum of US$250 for each day of their stay, and travel exclusively with a guide and driver. And you can only enter the country in the first place with an official tour operator or travel company.

While this might seem stifling and expensive — you’ll find no backpacker-style, independent travel here — it’s allowed this diminutive country to develop a sustainable, low-impact travel industry that poses no threat to its own cultural identity. Yes — even if you’re a widely experienced globe-trotter, Bhutan might just be one of the most singular cultures you’ll ever experience. And that’s aside from the remote Himalayan trekking on offer.

To cite a couple of examples: you’ll see all Bhutanese wearing traditional dress (another government regulation — but citizens do seem to take a real pride in doing so). Men sport gho (a tunic-like garment tied round the waist with a chord) and knee-high socks; women wear kira (a straight, wraparound dress and blouse). Even if you’re familiar with Buddhism, the branch followed in Bhutan is very different to what you may have observed in Southeast Asia. Men wear sashes whenever they enter dzongs (monastic fortresses) and temples, and the religion is far more ritualistic, including lots of bowing in prayer.

Climbing Mount Kinabalu and visiting the Maliau Basin, Borneo

You begin in cloudforest, passing frothing waterfalls and strange crimson carnivorous plants as you follow the muddy trail until it turns to clay and you emerge above the treeline. After staying one night in a hut, you start your summit walk in early-morning darkness, occasionally hauling yourself over barren granite slopes to reach the peak. Here you rest and watch the rising sun turn the thick quilt of surrounding cloud shades of dusky pink and peach. As the cloud lifts, the crags and canopy of Kinabalu National Park emerge.

Summiting one of Southeast Asia’s tallest mountains is no mean feat, but nor is it beyond the realms of most amateur hikers. The climb is not technical and the trail is well-signposted; it’s difficult to lose your way. However, steep drop-offs and the challenging roped section over bare rock face, plus the danger of altitude sickness, means that permits and private guides are required in order to ensure hikers’ safety. After 2015’s earthquake, permits have been reduced to 135 people per day, and must be purchased at least six months in advance. They also help to preserve the trail’s flora (including the Rothschild slipper, one of the world’s rarest orchids).

Those seeking to get truly off the beaten track can trek Borneo’s Maliau Basin. This near-impenetrable ‘lost world’ (similar in size to Singapore) of old-growth forest, including pristine hill dipterocarp forest, is naturally fenced in by high cliffs and only accessible via one route in and out. Permits are necessary to keep track of everyone entering this barely touched wilderness. In order to be granted one, trekkers must provide medical certificates to prove their fitness, as there’s no going back once you’re ensconced in the jungle here (save emergency helicopter).

Was this useful?