Tailor-made Jordan holidays shaped around your passions

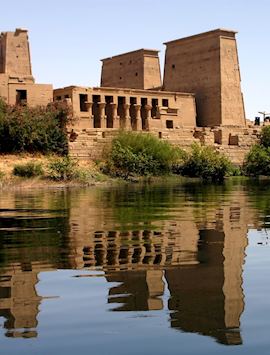

A crossroads for millennia, Jordan has faced endless waves of invaders, from ancient Romans to Ottomans and European crusaders. In their wake, these empires have left ornate churches, crusader castles and desert citadels, as well as the lost city of Petra. Our specialists return, time and again, to find the best ways to explore this timeless land. We can help you get away from the crowds at Petra, hike through the wind-carved wadis (valleys) of the Dana Nature Reserve, camp out under the desert stars or sip coffee with Bedouins.

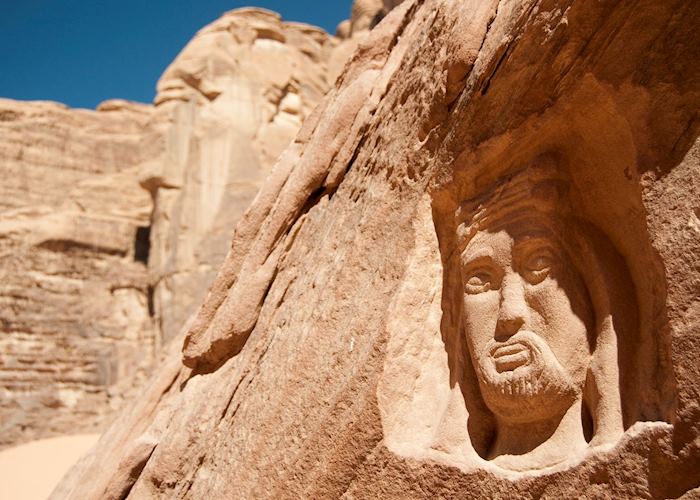

Despite its turbulent history, Jordan today is a safe, stable country that’s easy to navigate, making a holiday in Jordan a good introduction to the Middle East. The country offers you natural wonders, too, including the salt-crusted shores of the Dead Sea, coral reefs in the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Wadi Rum desert, where monumental rock formations tower over deep-red sands.

Suggested tours for Jordan

These tours give you a starting point for what your holiday to Jordan could entail. Treat them as inspiration, as each trip is created uniquely for you.

Suggested activities for Jordan

Whatever your interests, our specialists will build activities into your trip that connect to how you want to experience Jordan.

-

Full Day Tour of Jerash, Umm Qais & Ajloun ![View from Ajloun Castle]()

Full Day Tour of Jerash, Umm Qais & Ajloun

AmmanFull Day Tour of Jerash, Umm Qais & Ajloun

Located about an hour outside of Amman, Jerash is one of the real highlights of a trip to Jordan. It is one of the best-preserved Greco-Roman cities in the Middle East, although it traces its origins right back to Neolithic times.

View details -

Visit Pharaoh's Island ![Pharaoh's Island in the Gulf of Aqaba]()

Visit Pharaoh's Island

AqabaVisit Pharaoh's Island

Swim and snorkel around Pharaoh's Island before enjoying a delightful barbecue.

View details -

Seven sights of Wadi Rum jeep tour ![Wadi Rum, Jordan]()

Seven sights of Wadi Rum jeep tour

Wadi RumSeven sights of Wadi Rum jeep tour

This tour takes in seven of the sights of Wadi Rum, and is a detailed exploration of the deeper recesses of the wadi.

View details

Why travel with Audley?

- 100% tailor-made tours

- Fully protected travel

- Established for over 25 years

- 98% of our clients would recommend us

Best time to visit

Our specialists advise on the best months to visit Jordan, including information about climate, events and festivals.

Request our brochure

Covering all seven continents, The World Your Way shows you how you can see the world with us. It features trip ideas from our specialists alongside hand-picked stays and experiences, and introduces our approach to creating meaningful travel experiences.

Useful information for planning your holiday in Jordan

Modern Standard Arabic is the official language of Jordan, but you’ll mostly hear people speaking Jordanian Arabic in conversation. This is a local dialect that stems from Modern Standard Arabic but uses colloquial terms for some words that are different. Many Jordanians are able to understand and speak English, too, though you might not find this to be the case among the Bedouin people in places like Wadi Rum.

The currency of Jordan is the Jordanian dinar (JOD, د.ا), which is divided into 100 qirsh (sometimes called ‘piastres’) or 1000 fils. You’ll find banknotes in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, and 50 dinar, as well as coins in denominations of 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 piastres and 0.25, 0.5, and 1 dinar.

You can withdraw local currency from ATMs in all towns and cities, big and small. Credit cards are widely accepted in Jordan but you may struggle to use them in more remote rural areas like the desert.

We recommend trying a few of Jordan’s smaller mezze dishes like creamy baba ghanoush and a refreshing tabbouleh salad, followed by succulent grilled meat and pillowy flatbread. If you want something on the go, you could get a shawarma, thinly sliced seasoned lamb or chicken shaved into a pocket of flatbread and garnished with garlicky sauce. Similar to Lebanese cuisine, Jordanian food is marked with an earthy, citrus taste that stems from its classic blends of sumac, thyme, oregano, garlic, onion, and lemon.

To drink, you could try a black Arabic coffee infused with cardamom or a sweet mint tea. For something alcoholic, try sampling the local spirit, araq, a triple-distilled vine alcohol laced with liquorice-tasting aniseed. Just be aware that not all places you visit will sell or allow alcohol.

Tipping restaurant staff, drivers, and guides is expected in Jordan, and we recommend leaving around 10% in more upmarket restaurants. For smaller restaurants, anything from 500 fils to one dinar is about right. For guides, the amount you tip will depend on various factors, but we can help you work it out before you travel.

For the latest travel advice for Jordan, including entry requirements, health information, and the safety and security situation, please refer to the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office website.

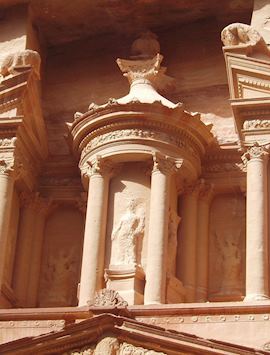

Visiting the living-rock ruins of Petra is one of Jordan’s most notable draws, but there’s a lot more to experience beyond exploring this ancient citadel, including camping on the terracotta-hued sands of Wadi Rum desert and floating upon the buoyant salt water of the Dead Sea.

We can also help you experience Jordan beyond its classic sights, diving deeper into the history and culture of this Levantine kingdom. For example, you could dine on traditional Jordanian fare within a cave near Petra once inhabited by Bedouins, forage for indigenous plants with a local expert in Umm Qais overlooking the Sea of Galilee, or try your hand at shepherding with a shepherd in the shrubby hills of Pella.

Jordan has many contemporary international hotels dotted around the country, including some more sumptuous options, but there are also a handful of distinctive stays you can experience during your trip. For example, you could gaze at the starry night sky from your domed desert tent in Wadi Rum, soak in the valley views at an eco-friendly guesthouse in Dana Biosphere Reserve, or enjoy a remote stay at an artistic rendition of a rustic Jordanian house snuggled into the hills of Pella.

Most people begin their journey in Jordan’s capital city of Amman, visiting the nearby 1st-century Roman ruins of Jerash before setting off for a desert-lined road trip to Petra, Wadi Rum, and the Dead Sea. We recommend spending at least a couple of days exploring each of these sites, and if you have more time, adding on a relaxing beach trip to the vibrant coral reefs of Aqaba or an outdoors adventure within the canyon-carved landscapes of Dana Biosphere Reserve.

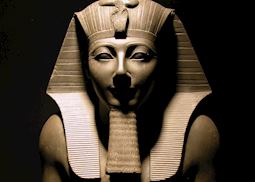

People often combine a trip to Jordan with a cruise along the Nile in Egypt or few days perusing the sacred city Jerusalem just across the border.

It takes around six hours to fly from the UK to Jordan’s capital city of Amman. We recommend flying with British Airways, Air France, Egypt Air, and a few other airlines, which we can advise on.

The time zone in Jordan is GMT+3 and there’s no longer daylight saving time there, so the clocks stay the same all year round.

Jordan is a small country, so the quickest and simplest way of getting around is by car. We can arrange a private driver for you who will likely stay with you throughout your entire trip. If you’d like to add on a trip to Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, you can drive over the border, or for Egypt, it’s just a short flight away.

Use our travel tool to find up-to-date visa and passport requirements for Jordan. Enter where you’re travelling to and from (including any stopover destinations en route or flight layovers), along with your intended travel dates and passport details, for a full list of requirements.

You should check with your doctor to see which vaccinations you’ll need for Jordan, but we recommend that you’re at least up to date with the vaccinations recommended for your home country. You can take a look at suggested vaccinations for Jordan on the Travel Health Pro website.

Going to Jordan during Ramadan can be challenging as many of the locals will be fasting during this time and shops and restaurants tend to be closed during the daytime. While you’re not expected to fast, it’s respectful to avoid eating, drinking, and smoking in public during daylight hours. You’ll likely need to eat in your hotel or at the back area of open restaurants away from the windows. That said, museums and archaeological sites remain open during Ramadan and tend to be quieter.

After the sun sets, the atmosphere shifts from placid to vibrant and celebratory as the streets come alive with people enjoying iftar, a meal that breaks the fast. It may be noisy until the early hours because people stay up to eat just before the sun rises again.

Jordan is a Muslim country, albeit less conservative than others, so it’s best to dress modestly to respect the local culture, no matter your gender. That means you should cover your shoulders and knees while out in public. We also recommend packing layers as the weather can change very quickly in Jordan, flitting between hot sun and rain showers. Finally, if you visit a mosque, women will need to cover their hair.

There’s no official dress code for Petra and women don’t need to cover their hair while walking around the ruins, but you should wear comfortable footwear as the trails can be uneven. While you can wear whatever you want, we recommend loose, comfortable clothing and layers, especially if you want to explore beyond the much-photographed Treasury.

No, it’s forbidden to photograph government and military buildings in Jordan, and it’s best to avoid capturing any bridges or canals that could be construed as having strategic significance.

Jordan in pictures

Our expert guides to travelling in Jordan

Written by our specialists from the viewpoint of their own travels, these guides will help you decide on the shape of your own trip to Jordan. Aiming to inspire and inform, we share our recommendations for how to appreciate Jordan at its best.

-

![My travels in Jordan]()

My travels in Jordan 2018

Your trip to Jordan could involve the monumental tombs of Petra, the sere desert landscapes of Wadi Rum and a visit to the cosmopolitan capital city of Amman. Get inspired by footage from Nick’s recent visit.

-

Family trips to Jordan ![Tracks in the sand at Wadi Rum]()

Family trips to Jordan

Family trips to Jordan

With ancient ruins, a rock-carved city, and a cinematic red-sand desert, Jordan is a great option for families who want to embrace adventure (without sacrificing comfort). Here, Audley specialist Olivia outlines her ideal Jordan family trip.

Read this guide -

Amman for more than one night ![The Roman Theatre, Amman]()

Amman for more than one night

Amman for more than one night

Jordan’s capital city is much more than just a rest stop on your way to the country’s many ancient sites. It invites you to explore the Roman amphitheatre, take a cooking class in a family kitchen and see the oldest known human statues.

Read this guide -

Explore the mysteries of Petra ![The Monastery, Petra]()

Explore the mysteries of Petra

Explore the mysteries of Petra

A hidden city that’s carved into sandstone cliffs, Petra was one of the wonders of the ancient world. Jordan specialist Nick offers a guide to the history and important sites in this vast city.

Read this guide -

The King's Highway in Jordan ![Kerak Castle]()

The King's Highway in Jordan

The King's Highway in Jordan

Travelling the King's Highway in Jordan means seeing 5,000 years of history. Visit sites of the Holy Land, the churches at Madaba and Mount Nebo, the castles of Kerak and Shawbak, as well as the ancient city of Petra.

Read this guide