By Spain specialist Allan

From Montserrat’s lofty mountain monastery to the royal crypt under El Escorial, Catholic architecture dominates the Spanish landscape. Though the church’s grip on Spain can seem timeless and secure, the reality is more complicated than it might appear at first glance. Many of the country’s important chapels and great cathedrals were built on Moorish mosques. These were themselves once the site of Visigoth churches, which were in turn built on the remnants of Roman temples.

There are nearly 100 cathedrals in Spain and innumerable chapels, monasteries and churches, but a few stand out either for their beauty or historical importance. You can include a few on any trip to Spain, including this week-long visit to Barcelona and Madrid.

Moorish majesty at the Mezquita, Córdoba

The most obvious example of Spain’s complicated past is the great mosque-cathedral of Córdoba.

The mosque itself was and remains the most important Muslim structure in all of Western Europe, built shortly after the invasion of 711. Though the exterior is a bit austere, even plain — Moorish architects preferred to save the elaborate decor for the interior — I suggest taking a walk around the structure before you go in to appreciate its massive size and early-medieval horseshoe arches.

To get inside, you’ll walk past a bell tower, which was converted from a minaret, and enter a sun-drenched courtyard, filled with a grove of orange trees. If you’re visiting in the spring, when the trees burst forth in white blooms, the air will be thick with the flowers’ syrupy-sweet perfume.

Beyond that, you’ll find the prayer hall — a vast forest of pillars topped with red-and-white-striped arches. The columns, arranged in mathematically precise rows that seem to recede into infinity, make the shadowy hall seem even larger. The space is designed to befuddle your sun-dazzled eyes, and it can take several minutes to adjust to the lower light.

But if you look closely, you’ll see that some of the pillars are repurposed from the buildings that predated the mosque — a Roman column here, a honeycomb-textured Visigoth column there. The hall was expanded over time and the earlier arches are built from alternating portions of concrete and brick, but latter-day stripes are merely painted.

The focal point of all this magnificence is the mihrab, a shimmering gold-tiled prayer niche that’s supposed to face east, toward Mecca. (It doesn’t. Though Mecca is southeast of Córdoba, the mihrab faces almost due south, giving rise to a panoply of academic debates and outlandish theories.)

Stepping from the dim prayer hall, you’re suddenly faced with a soaring, bright-white Catholic transept. For me this contrast always remains startlingly abrupt, even though I’ve seen it many times. Built in the 16th century, the chapel reflects an array of styles, including Baroque, Renaissance and Mannerism. The dark wooden choir stalls are a masterwork of intricately carved mahogany.

I suggest also taking time to visit the small, often-overlooked Gothic chapel, which dates back to the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella and was the first Christian addition to the mosque.

Gothic glory at Capilla Real de Granada

The final resting place of Spain’s founding monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella, is the Capilla Real de Granada, located two hours south of Córdoba. The monarchs chose to be buried in Granada, the last city captured from the Moors during the Reconquista, rather than their home kingdoms of Aragon and Castilla.

The cathedral boasts a richly ornate Renaissance façade and a glimmering gold-and-white interior. Accessed by a different entrance, the monarchs’ tombs lie in a flamboyant Gothic mausoleum to the side of the main cathedral, behind a towering, wrought-iron grill.

The elaborate marble tombs stand in front of a vast, heavily gilded altarpiece that features detailed figures representing scenes from the life of Christ and Spain’s Catholic kings. All this pomp, however, is a bit misleading. If you want to see the actual monarchs, you’ll have to head downstairs to see two small, simple lead coffins in a crypt under the glorious tombs.

A great monstrance at the Toledo Cathedral

One of the three great Gothic cathedrals of Spain, Toledo’s cathedral was where Ferdinand and Isabella originally intended to be buried, before Granada was captured. It’s a massive, asymmetrical structure with a façade that reflects a mishmash of styles, including Renaissance, High Gothic and Mudéjar, the singular Spanish style influenced by Islamic design cues. This is also the seat of the Catholic Church in Spain.

Inside, you’ll find a soaring forest of pillars that branch out into a rib-vaulted ceiling. The interior is so cluttered that it can be hard to tell, but the sacristy is one of the country’s greatest repositories of art. If you peer through the dim light, you’ll see works by El Greco, Velázquez, Goya, Zurbarán, Titian and Raphael.

The two highlights here are undoubtedly the altarpiece as well as La Gran Ostensoria de Toledo.

Reaching to the ceiling, the altarpiece is an elaborate display that depicts Christ’s life in finely painted wooden figures staged in gilded settings.

La Gran Ostensoria de Toledo, also known as the Great Monstrance of Arfe, is a vessel for holding the eucharist that stands 3 m (10 ft) tall. Heavily encrusted with gems, it’s made from silver and what’s said to be the first gold that Columbus brought back from the New World.

A grill-shaped palace in San Lorenzo de El Escorial

An hour north of Madrid, at the base of the mountain range that cordons off the north part of the country, El Escorial is a massive complex that includes a palace, library, basilica and mausoleum, as well as the final resting place of most of the Spanish monarchs who came after Ferdinand and Isabella.

Built in the 16th century by Filipe II, this stone behemoth is an exemplar of Renaissance symmetry. It’s so huge that, from certain approaches, you can see the spires of its towers 45 minutes before you arrive at the palace itself. Though it looks like a quadrangle, it’s actually shaped like a cooking grill, a nod to its patron saint Lorenzo, a martyr who was roasted alive by the Romans.

The sober basilica boasts a dome that’s similar to St Peter’s in Rome, though the ceiling is supported by heavy and simple granite pillars, a stark contrast to the ebullient Corinthian columns of its Italian counterpart. The jasper-and-red-granite altarpiece, built on a similarly huge scale, is decorated with subdued bronze statues.

But the big draw here is the crypt where most of Spain’s kings and queens are laid to rest. It’s an unexpectedly small space in a such a huge complex, and the late monarchs are packed in tightly. There’s only space for two more royals — when the current king dies, no one is quite sure where he’ll rest.

Music and mountains at Santa Maria de Montserrat Monastery

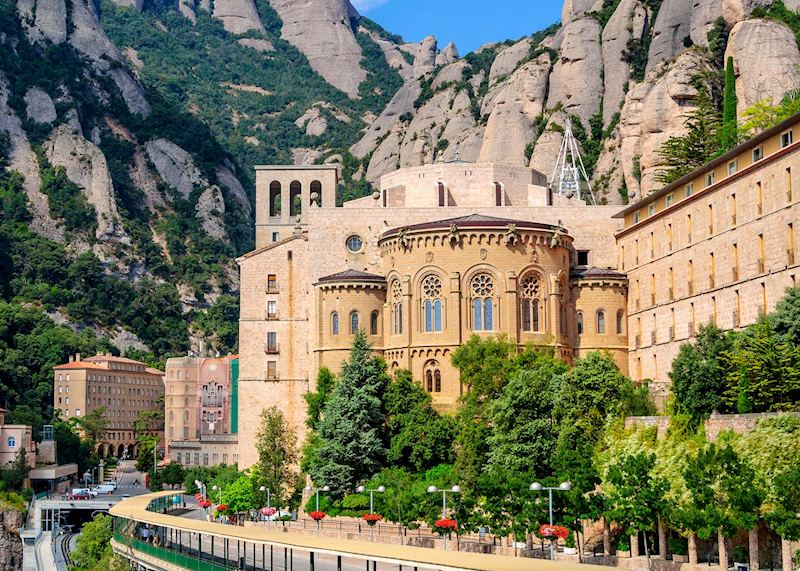

The primary pilgrimage site for Catalans for a millennium, Monestir de Montserrat (Montserrat Monastery) sits on a plateau high in a mountain range near Spain’s east coast. It’s home to one of the world’s most prestigious boys’ choirs as well as an early medieval statue of La Moreneta (the Black Virgin), the patron saint of Catalonia.

The monastery itself is an austere, almost fortress-like building, rebuilt in the 18th century after Napoleon destroyed it. About two dozen Benedictine monks live and work here, though they don’t interact with either visitors or the many local pilgrims who flock to touch the statue’s orb and ask for the Virgin’s blessing.

Bulbous and serrated, the mountains are located about an hour’s drive from Barcelona and I suggest timing your visit to hear the choir’s daily performance at 1pm. After hearing their soaring treble voices, you can either hike or take a short ride in the funicular to the peak, Sant Joan. From there, you’ll have a view over the green hills of Catalonia.

Fat geese and folk dancing at the Barcelona Cathedral

Located on Spain’s Mediterranean coast, Barcelona is home to la Sagrada Familia, Gaudí’s modernist masterpiece. Its gargantuan size and swirling, dripped-sand-castle design definitely make it a highlight of any visit to the city. But I prefer the Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Saint Eulalia, more commonly known as Barcelona Cathedral.

Catalonia’s great Gothic masterpiece, it’s one of the few churches in the city to survive the civil war unscathed. Most of the building’s exterior is a bit restrained, with the exception of the richly decorated main façade, which was added in the late 19th century.

The clean Gothic lines continue inside, its uncluttered look giving you room to appreciate the elegance of the construction. The fluted columns soar upwards, drawing your eye to the vast arched vaults of the ceiling.

You’ll see similar construction in the adjacent cloister, where vaulted galleries surround a courtyard known as the Well of the Geese. Here, a baker’s dozen of plump white geese live pampered lives in a garden of magnolias, medlars and palms — the number is a tribute to the cathedral’s patron saint, Eulalia, who was martyred at the age of 13. The geese will waddle right up to you at the railing.

If you’re visiting on a Sunday morning, look for folk dancers in the plaza by the stairs performing the sardana, a traditional Catalan circle dance.

Read more about trips in Spain

Start thinking about your experience. These itineraries are simply suggestions for how you could enjoy some of the same experiences as our specialists. They're just for inspiration, because your trip will be created around your particular tastes.

View All Tours in Spain